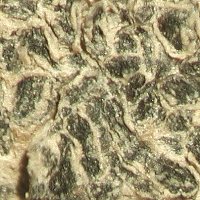

CRYPTOBIOTIC

CRUST is also called BIOLOGICAL SOIL CRUST.

These are communities of

cyanobacteria, green algae, lichens, mosses, liverworts, and microorganisms

that colonize the surface of bare soil. "Cryptobiotic" means "hidden

life." Crusts often go unnoticed unless they are very extensive or

colorful, and some do not even look alive. But they are vital

to the health of soils and ecosystems. Cryptobiotic crust is best

known (and probably most studied) from the protected lands of the national

parks of the Colorado Plateau, where it forms dark lumpy patches on the

red soil. But it is equally important to desert, prairie, and tundra

ecosystems, and also colonizes bare ground in humid temperate environments.

The most complex and spectacular "old growth" crusts take decades to develop.

They are miniature forests with dozens of species of cyanobacteria, green

algae, mosses, and lichens over a dark layer of organic-rich soil.

The damp soil is alive with earthworms, snails, millipedes, insects, and

microorganisms, and nourishes grasses, wildflowers, and even trees.

WHERE CAN I FIND CRUSTS?

You must look beyond the

more obvious landscape features and learn to see in a different way.

Seek subtle differences in color and texture on bare soil between the rock

outcrops, among a scatter of pebbles, or under thorny trees and inconspicuous

shrubs. You will discover a tiny, intricate and surprisingly beautiful

hidden world.

WHAT GOOD ARE THEY?

Crusts hold the soil in

place and protect underlying sediments from erosion. They pioneer

soil development on bare inorganic sediments, absorbing water and enriching

the surface with nutrients and organic matter. This creates a favorable

environment for seeds to germinate and for insects and other soil organisms

to live. Crusts enable the land to recover more quickly after a fire.

Crust organisms such as lichens and dried mosses are vulnerable to burning

and can be killed even in a relatively cool, fast-moving grass fire.

But the cyanobacteria often survive. Grasses, shrubs, and crust organisms

regenerate faster in this living substrate than they would on barren ground.

CRYPTOBIOTIC CRUSTS ARE

FRAGILE.

They are extremely susceptible

to destruction by crushing and trampling. Once damaged, they may

take many years to grow back. Meanwhile, several feet of sediment

may be washed or blown away. Areas that have been stripped of cryptobiotic

crusts are vulnerable to erosion, flooding, deflation, dust storms, invasion

of exotic weeds that thrive on disturbed soil, and/or chemical impoverishment

due to loss of organic material and precipitation of evaporite minerals. Hikers

and horseback riders who venture off established trails can damage crusts.

This is a localized issue that can be reduced through education and regular

trail maintenance. Offroad vehicles venturing off established routes are a more widespread and serious

problem.

PUBLIC-LANDS RANCHING IS

A MAJOR THREAT to cryptobiotic crusts and nearly all Western U.S. plant

communities. Cattle strip vegetation and leave only the most inaccessible

crevices untrampled. Cryptobiotic crust cover on public land is often

measurable only in square inches, usually under shrubs or in cracks between

rocks that are too steep for cattle. Well-developed crust communities

flourish only where cattle are excluded. The ranching culture perpetuates

several myths about crusts: vast areas of desert are thought to be

"naturally" devoid of crusts, and crusts may be deliberately destroyed

because they "compete" with grass or "prevent" grass from growing.

Specimens illustrated

are from public land in southern Arizona: State, USFS, BLM, and Saguaro

National Park. |